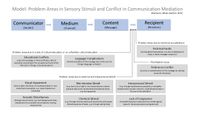

Model: Problem Areas in Sensory Stimuli and Conflict in Communication Mediation.

By Prof. Dr. Alfred-Joachim Hermanni

2019

1 Introduction

From a historical perspective, the 1949 sender-receiver model by Claude E. Shannon and Warren Weaver shaped the understanding of communication as a process of conveying information. On a technical level, the transport of information takes place as a linear, one-way process between a sender/transmitter (who encodes the information into material signals) and a receiver (who decodes the signals).

Originally, the model was developed from the perspective of the telephone medium in order to recognize potential disturbances in signal transmission (e.g. through noise, distorted radio waves or image interference). In this context, a communication was successful if the technical signal transmission was neutral and free of interference and the transmitted message was identical to the received message.

Technical disruptions in the transmission of messages are much less common today than they were in the 20th century, thanks to modern digital transmission technologies. Nevertheless, occasional limitations may occur, such as poor cell phone reception despite a Wi-Fi connection or external interference with FM radio.

Apart from the well-known technical disruptions in the encoding and decoding process, another dimension is increasingly coming into focus: What role do sensory stimuli play in the context of communication disruptions? And could it be that the human senses play a previously underestimated role in information transmission – with implications for hitherto little-researched sources of disruption in communication?

2 Can human senses be described as media?

Based on an expanded understanding of media and communication theory, as laid out by McLuhan (1964), Krämer (2008), and Noë (2004), the human sensory organs can be understood as original media. They perform a central mediating function between physical environmental stimuli and subjective perception, thus forming the basis for all media reception. In this function, they are not only receptive, but also selective, interpretative, and structuring – they actively filter, weigh, and shape the perception process. Against this background, the sensory organs appear as “filter media” that significantly influence what and how medially conveyed content is perceived, cognitively processed, and emotionally evaluated.

Marshall McLuhan (1964) argues that media are not limited to technical artifacts, but should be understood as extensions of human sensory abilities: “All media are extensions of some human faculty – psychic or physical” (McLuhan, 1964, p. 26). From this perspective, the eye is just as much a medium for visual stimuli as the camera or the ear is for acoustic signals – the sensory organs themselves become mediating media for the construction of reality.

This position is supported by approaches from modern cognitive science, in particular the theory of embodied cognition. Perception is not understood here as a purely receptive process, but as an active activity. Alva Noë puts it bluntly: “Perception is not something that happens to us, or in us. It is something we do” (Noë, 2004, p. 1). In this sense, the senses are not mere channels, but active media of cognitive world exploration.

Sybille Krämer (2008) understands media in a general sense as those instances that make transmission possible in the first place. She argues: “A medium is not what transmits, but what makes transmission possible in the first place” (Krämer, 2008, p. 28). In doing so, she places the mediating role of the senses at the center of an expanded media ontology.

Communication psychology also provides evidence of such an expansion of the concept of media. Pörksen and Schulz von Thun (2008) emphasize: “Media do not begin with technology, but with the ability to perceive.” (p. 57). Perception is therefore itself a fundamental condition of media, not merely a passive counterpart to technical forms of transmission.

Against this theoretical background, the sensory organs can be interpreted as constitutive media of communication and perception of reality. They do not stand outside media processes, but form their first, physically based level.

3 Problem areas of sensory stimuli and conflicts in communication mediation

The media-theoretical view of human sensory organs as mediating instances raises the question of the extent to which the information content of a message can be impaired or distorted in human communication by disruptive influences at the level of sensory perception.

According to Alfred-Joachim Hermanni, discrepancies between the encoded and decoded message occur in the phases of the communication process, especially since, in addition to language, non-verbal signals such as facial expressions and gestures are generally sent and human senses influence the transfer process between transmission and reception. Hermanni attempts to identify universal sources of interference in a sender-receiver transmission and distinguishes between four major problem areas:

- Firstly, problem areas that arise from technical complications in signal transmission, including background noise or faulty message reception (see sender-receiver model according to Shannon and Weaver).

- Secondly, problem areas that can arise from a lack of or foreign cultural education. These include educational conflicts (missing knowledge or final certificates, lack of education according to the competency levels of the PISA tests, communication partners come from different cultural backgrounds or belong to different generations, as well as linguistic complications (incorrect or inadequate interpretation of the message due to the use of a foreign language or dialect, translation errors from one language to another).

- Thirdly, there are problem areas that can arise from external and interpersonal stimuli. These include chemical stimuli, skin-intensive stimuli, acoustic impairments and visual impairments:

- Visual impairment (due to light; restriction of visual perception in non-verbal communication, e.g. due to visual impairment, blindness, color weakness).

- Acoustic impairments (due to sound waves, e.g. loud background noise, distractions from parallel conversations, background noise from people, hearing impairments). This can lead to a cocktail party effect (also known as intelligent or selective hearing), in which the human sense of hearing extracts the components of a particular sound source from the mixture of background noise (see Cherry).

- Skin-intensive stimuli (e.g. due to very high or low temperatures, intense touch and pressure, acceleration and mechanical strain, e.g. during sports).

- Chemical stimuli (e.g. due to intense odors such as perfume and sweat, due to distracting senses of taste, e.g. due to eating during the transmission process).

- Interpersonal stimuli (e.g. spontaneous sympathy or antipathy towards other people; the external, visual attractiveness of people in the eye of the beholder; a lack of distance for comfort and/or signals from individuals that they exchange by maintaining a certain distance from one another).

- Lack of congruity (agreement) between verbal (speech) and non-verbal signals (facial expressions and gestures).

4. Fourthly, the problem area of prioritization. People show a particular interest, a preference or a marked tendency towards topics and rank these according to their personal preference. Or they favor certain people and rate their information higher than that of other persons involved in the communication. Or they are pressed for time and only want to hear a summary of the information.

If communication deficits are present due to sources of interference in a sender-receiver transmission, these can be reduced and possibly avoided if agreements are made in advance to encode and decode information in a way that is appropriate for the target group. For example, technical terms and setting priorities could be avoided and the interpersonal communication process (interpersonal interaction) could be regulated.

However, an exchange of information does not necessarily have to take place between two people, but can also involve communication between humans and technology. Here, for example, we are thinking of the areas of “augmented reality”, i.e. the perception of real images with additional information, or “human-computer interactions” (e.g. a person communicates with the vehicle via the voice control of an on-board computer). Corresponding disruptive processes within the problem areas can be attributed to technical complications.

Source: Hermanni, Alfred-Joachim (2019)

Bibliography

Cherry, C. E. (1953). Some experiments on the recognition of speech, with one and with two ears. In: Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. Band 25, 1953, S. 975–979.

Hermanni, A.-J. (26.12.2019). Problemfelder sensorische Reize und Konflikte in der Kommunikationsvermittlung. URL: https://www.wissensbank.info/EMPIRISCHE-SOZIALFORSCHUNG/Problemfelder-Kommunikationsvermittlung

Krämer, S. (2008). Medium, Messenger, Transmission: A Short Metaphysics of Mediality. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

McLuhan, M. (1964). Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Noë, A. (2004). Action in Perception. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Pörksen, B., & Schulz von Thun, F. (2008). Kommunikation als Lebenskunst: Philosophie und Praxis des Miteinander-Redens. Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt.

Shannon, C. E./Weaver, W. (1949). The Mathematical Theory of Communication. In: The Bell System Technical Journal 27 (3-4), pp. 379-423, 623-656. Shannon and Weaver were mathematicians at the Bell Telephone Company.